Detailed Overview: 30-Minute Read

Promoting Brain Health

Discover the ways you can promote brain health and reduce your risk of developing dementia.

Topic:

Introduction

Basic facts about the importance of promoting brain health and modifiable risk factors.

Why is brain health important?

Promoting brain health is important because our brain is the control centre of our body and plays a critical role in our overall well-being. The brain controls everything from our thoughts, learning and memory, language, visual and spatial ability, emotions, and behaviour; to our movement, senses, and bodily functions. Maintaining good brain health can help prevent or delay the onset of cognitive decline and brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Recent research has shown that there are several actions you can take to promote brain health and delay or prevent cognitive impairment.

It is never too early or too late to reduce your risk of dementia.

What can affect your brain health?

Brain health can be affected by age-related changes in the brain, injuries such as stroke or traumatic brain injury, disorders such as depression, substance use disorders or addiction, and diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia. While some factors affecting brain health cannot be changed, there are many lifestyle changes that might make a difference.

What do we mean by dementia risk reduction?

There are three main ways we think of dementia risk reduction:

- Decreasing the lifetime risk of dementia

- Delaying the onset

- Possibly slowing the progression (this is sometimes called ‘secondary prevention’, as the person already has the disease)

What do we mean by risk factors?

A risk factor is something that increases the chance of developing a disease. We can divide risk factors for dementia into two kinds: non-modifiable and modifiable.

Non-modifiable risk factors are ones that are outside of your control, like your age or your genetic make-up. Modifiable risks are ones that you can do something about, and we’re going to focus on those in this detailed overview.

The impact of lifestyle on brain health

Recent research has shown that there are several actions you can take to promote brain health and delay or prevent cognitive impairment. These actions relate to modifiable risk factors that you can change through healthy lifestyle behaviours.

What are the important modifiable risk factors for dementia?

Modifiable risk factors are the behaviours, lifestyle choices, and health conditions that can be changed in order to reduce the risk of developing certain diseases or health problems. These risk factors include things like smoking, poor diet, lack of exercise, excessive alcohol consumption, and high blood pressure, among others. By making changes to these modifiable risk factors, you can improve your overall health and reduce your risk of developing certain diseases or health problems like dementia and cancer.

How much can I reduce the risk?

This is an active area of research, but The Lancet Commission identified several modifiable risk factors that might prevent or delay up to 45% of dementias. Two other recent studies found that engaging in 2-3 healthy lifestyle behaviours could lower your risk of Alzheimer’s disease by 37%, while doing 4-5 healthy behaviours could lower your risk by 60%.

So, the more of these factors you can incorporate into your life, the better it is for your overall brain health.

Modifiable risk factors aren’t the only type of risk factors for dementia, there are also ‘non-modifiable’ ones. Non-modifiable risk factors are ones that can’t be changed like aging, family history, or genetics. For example, the odds of developing dementia increases with age; and there are a small number of dementias that run in families and are often associated with particular genes.

It’s important to remember that most cases of dementia aren’t related to family history or specific genetic disorders. And a significant amount of dementia may be associated with several modifiable risk factors. There are also certain environmental factors – such as lower levels of education in early life – that are important things for us to try to address as a society, but might not be things that you can modify now.

Ways to promote brain health

In the following sections, we’re going to focus on those things that you can change to promote brain health, where there is evidence of dementia risk reduction. Many of these factors are also associated with other health benefits, such as reducing your risk of cancer or other chronic diseases.

The World Health Organization and the Lancet Commission and others have examined the evidence and made recommendations for several ways in which people can promote brain health and reduce their risk of developing dementia. These include the following topics, that we’ll be covering below:

- Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep

- Weight management, diet, and nutrition

- Blood vessel health

- Smoking and alcohol

- Cognitive (brain) and social activity

- Hearing and vision loss

- Other health conditions and medication adverse effects.

Key points from this topic

- There are several healthy lifestyle changes that you can do to promote brain health and reduce your risk of dementia

- The more you can implement, the better

- These healthy lifestyle habits are good for your overall health in addition to promoting brain health and reducing your risk of other chronic conditions like cancer

Topic:

Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep

Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep are important to your well-being and brain health.

Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep

Many scientific studies have shown that exercise is great for the brain. It helps to release chemicals in the brain that are responsible for maintaining and improving brain health. There are many reasons to exercise, such as: improved bone health, lower risk of heart disease, improved mood, and decreased risk of falling, to name a few examples. Maintaining your brain health is just one more good reason to exercise.

Studies have found that people who exercise the most throughout mid-life have the lowest chance of developing dementia when they get older. Both aerobic exercise (like running, jogging, or brisk walking) and resistance training (muscle strengthening exercises) have been linked with better brain function immediately after exercise, as well as over longer periods of time.

The Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults Aged 65+

The Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) outline specific recommendations for older adults to move more, reduce sedentary time, and sleep well. Adults aged 65 years or older should participate in a range of physical activities (e.g., weight bearing/non-weight bearing, sport and recreation) in a variety of environments (e.g., home/work/community; indoors/outdoors; land/ water) and contexts (e.g., leisure, transportation, occupation, household) across all seasons. Adults aged 65 years or older should limit long periods of sedentary behaviours and should practice healthy sleep hygiene (routines, behaviours, and environments conducive to sleeping well).

Physical Activity

- Accumulate at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, in bouts of 10 minutes or more.

- Add muscle and bone-strengthening activities using your major muscle groups, at least two days per week.

- If you have mobility issues, activities to enhance balance to prevent falls are also recommended.

- Include several hours of light physical activities, including standing.

Remember, the key to any exercise program is to find something you enjoy so that the odds increase that you’ll stick with it.

Sleep

- Get 7 to 8 hours of good-quality sleep on a regular basis, with consistent bed and wake-up times

Sedentary Behaviour

- Limit sedentary time to 8 hours or less

- no more than 3 hours of recreational screen time, and

- try to break up long periods of sitting as often as possible.

Remember, the goal is progress, not perfection: progressing toward any of the above goals will result in some health benefits.

Please note as we age, we may need to be careful about starting exercise routines. Visual problems, hearing problems, heart disease, lung disease, muscle weakness or balance issues, and other conditions may make exercise unsafe. When possible, consider group exercise classes specifically designed for you. It is always safest to consult with your physician and/or physiotherapist, athletic therapist, or recreational therapist before starting new exercise routines and make sure you’re on the right track.

The link to the CSEP 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Ages 65+ is in our curated resources or here; or you can download the guidelines here.

More about sleep

If you have chronic troubles sleeping or insomnia, you may have thought about using over-the-counter sleep aids or prescription medications like sleeping pills. Unfortunately, many sleeping pills are not that effective and may be associated with adverse effects. These adverse effects may worsen your brain health, as well as things like balance.

There are very effective non-medication approaches to help with sleep, including developing better sleep habits (often known as good ‘sleep hygiene’). An effective alternative way to manage insomnia is through Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (or CBT, often called CBTi when used for insomnia specifically).

A good resource with information about insomnia and CBTi is the Sleepwell website from Dalhousie University researchers. They also have excellent evidence-based recommendations for self-help books, tools, and apps.

Key messages from this topic

- Move more, including aerobic exercise and strength-training

- Reduce sedentary time

- Sleep well

- if you do have sleep problems, consider non-drug approaches like good sleep hygiene and CBTi

Topic:

Weight Management, Diet, and Nutrition

Being overweight, diet, and nutrition can all have an impact on brain function and health.

Weight management

Being overweight can directly impact your physical mobility and is linked to several medical complications, many of which can have an adverse effect on our brain health, such as diabetes or high blood pressure. Body Mass Index (or BMI) and waist circumference are the measurements used to determine if a person is overweight or obese.

People who are obese in midlife have an increased risk of dementia compared to those with healthy body weight. Obesity is also linked to type 2 diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Some evidence suggests that interventions aimed at weight loss could improve cognitive functions like attention, memory, and language.

If you are overweight and don’t know where to start, ask your doctor about consulting a dietitian to work out a plan that is best for you. Managing your nutrition and following the physical activity guidelines will help you to manage your weight in the long run. A balanced diet is not only important for weight management but is also an important factor for overall brain health.

Diet and nutrition

What we eat can have a profound effect on our brain function. Aside from eating a well-balanced diet, certain diets – in particular, the Mediterranean Diet – have been associated with many health benefits, such as a decreased risk of heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease. In some studies of people at risk for dementia, people who ate a Mediterranean diet improved their brain function by a moderate amount.

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean Diet is exactly what it sounds like; common types of food that are consumed in many Mediterranean countries like Greece and Italy. The Mediterranean Diet consists of the following:

- Eating mostly plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes and nuts

- Replacing butter with healthy fats such as olive oil and canola oil

- Using herbs and spices instead of salt to flavour foods

- Eating fish and poultry at least twice a week

- Limiting red meat to no more than a few times a month

- And optionally drinking red wine in moderation

DASH and MIND Diets

A low-salt diet called Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) has also been shown to deliver significant health benefits. Studies testing the DASH diet found that it lowers blood pressure, helps people lose weight, and reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Yet another eating pattern that may support healthy aging is the MIND diet, which combines a Mediterranean-style eating pattern with DASH. It’s essentially the Mediterranean Diet with the addition of other foods that are high in antioxidant properties such as berries. Researchers have found that people who closely follow the MIND diet have better overall cognition — the ability to clearly think, learn, and remember — compared to those with other eating styles.

Learn more about the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan.

Brain Health Food Guide

The Brain Health Food Guide is an evidence-based approach to healthy eating for the aging brain developed by Dr. Matthew Parrott in collaboration with members of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA). It contains some excellent healthy diet recommendations aligned with the Mediterranean diet in a practical 2-page brochure.

Download the Brain Health Food Guide

Vitamins, supplements and antioxidants

Vitamins – Unless tests show you genuinely lack specific vitamins (for example, a true Vitamin B12 deficiency), supplementing doesn’t help. Recent research has found an association between vitamin D supplementation and reduced risk of developing dementia, but more research is required in this area before recommending supplementation for dementia prevention. Studies have been done showing no benefit for supplementation with vitamin E, vitamin B12, selenium, ginkgo, ginseng, multivitamins and many others.

Coconut oil – There was some thought that by changing the brain’s fuel source (from sugars to fats), that we could somehow improve brain function. The idea behind consuming coconut oil is precisely that. Unfortunately, at this time, there’s not sufficient scientific evidence to support this idea, and we therefore can’t recommend the consumption of coconut oil for brain health.

Key messages from this topic

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Reducing obesity can help with a number of conditions in addition to helping to promote brain health

- Diet changes can have a powerful effect on brain health (and other health benefits)

- check out the Mediterranean diet or the Brain Health Food Guide

- Don’t waste your money on unnecessary vitamins or supplements unless your doctor has identified an actual vitamin deficiency or recommended supplementation for some other health reason (e.g., vitamin D or calcium for your bone health)

- As with many lifestyle changes, start with small changes that seem manageable so you can maintain them in the long run

Topic:

Blood Vessel Health

High blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes can all impact your brain health.

Blood vessel health

Because damage to the blood vessels in the brain can cause dementia or strokes, it’s very important to maintain good blood vessel health. You can do this by monitoring and controlling blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and diabetes. Managing these factors can decrease your risk of developing dementia, having heart attacks or strokes, and may play a key role in protecting brain health.

High blood pressure (hypertension)

High blood pressure or hypertension can be associated with strokes and increased risk of vascular dementia. Managing high blood pressure can reduce your risk of dementia. High blood pressure is generally defined as a blood pressure over 120/80 mm Hg. You may hear your health care provider refer to ‘systolic’ or ‘diastolic’ blood pressure; these refer to the top and bottom numbers of your blood pressure. The top number is called the ‘systolic’ blood pressure, and the bottom number is called the ‘diastolic’ blood pressure.

Blood pressure targets

For most people, the top number (systolic) should be less than 140 and the bottom number (diastolic) should be less than 90. However, for some people with diabetes, the target might be less than 130/80 mm Hg. For others who might be at higher risk of heart disease, or for some older adults or those who are frail, the targets might be different.

According to the Lancet Commission report on dementia prevention, the evidence around dementia risk reduction says you should aim to maintain a systolic blood pressure (top number) of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around 40 years old.

Talk to your doctor about the best blood pressure target for you in order to balance the benefits of managing your blood vessel health, while ensuring that you are not running into adverse effects of your blood pressure getting too low.

Managing high blood pressure

There are non-medication things that you can do to help manage high blood pressure, including some of the other lifestyle factors that we’ve mentioned above, such as:

- Diet

- Exercise

- Reducing alcohol consumption, as well as

- Stress reduction

Medications – known as anti-hypertensives – are often needed if non-drug approaches can’t bring the blood pressure to a reasonable target. Sometimes people might need more than one class of anti-hypertensive drug. At this time, anti-hypertensive drug treatment for hypertension is the only known effective preventive medication for dementia. (Although there is some new research on medications for diabetes that is also showing promise.)

Want to learn more about high blood pressure and hypertension?

Check out these 3 videos from the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal about:

- Healthy blood pressure targets

- Effective ways to lower high blood pressure without medication

- Treating hypertension: lowering your blood pressure with medications.

You can also learn more about high blood pressure, choosing a blood pressure monitor, and tracking your blood pressure on the Hypertension Canada website.

Diabetes and hemoglobin A1C test

Diabetes can impact your blood vessels, and increase your risk of blood vessel damage and dementia. Conversely, good management of your diabetes can help to reduce your risk of dementia.

A hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) test is a blood test that shows what your average blood sugar (glucose) level was over the past two to three months. Your A1C test result is given in percentages. The higher the percentage, the higher your blood sugar levels have been:

- A normal A1C level is below 5.7%

- Prediabetes is between 5.7 to 6.4%. Having prediabetes is a risk factor for getting type 2 diabetes. People with prediabetes may need retests every year.

- Type 2 diabetes is above 6.5%

- If you have diabetes, you should have the A1C test at least twice a year.

The A1C goal for many people with diabetes is below 7%. For older adults with multiple medical conditions the goal is to keep the A1C less than 8%.

It may be different for you. Ask what your goal should be. If your A1C result is too high, you may need to change your diabetes care plan.

It’s important to balance the benefits of maintaining a good A1C level with the risks of low blood sugars or the side effects of multiple medications.

Diabetes and eye health

Diabetes is also associated with several eye conditions, including diabetic retinopathy, which leads to vision loss. New evidence shows that untreated vision loss is associated with an increased risk of dementia. Diabetic retinopathy can be prevented or its progress slowed with consistent blood sugar management and a healthy lifestyle.

Managing diabetes

There are non-medication things that you can do to help manage diabetes, including some of the same lifestyle factors that we’ve mentioned above, such as diet and exercise.

Many people may also require medications to manage their diabetes if non-drug approaches can’t bring the blood sugars or HbA1C to manageable levels.

Want to learn more about prediabetes and diabetes?

Check out these 3 videos from the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal about:

- Diabetes: Types, tests and what to do if you are at risk

- Prediabetes? How to delay or prevent type 2 diabetes

- Type 2 diabetes: Can it be reversed?

You can learn more about diabetes on the Diabetes Canada website.

High cholesterol (dyslipidemia)

In addition to its impact on blood vessel health, there is new evidence that high LDL cholesterol (also referred to as ‘bad cholesterol’) is also an independent risk factor for dementia.

Diet, exercise, and weight management are non-medication approaches to high cholesterol. If those are not effective in lowering your cholesterol, then there may be a role for cholesterol-lowering drugs like statins or others.

Unlike anti-hypertensives, there is currently no evidence that statin medications reduce the risk of dementia on their own.

Key points from this topic

- Check your blood pressure and manage high blood pressure

- Ask your doctor if you should be assessed for diabetes

- If you have diabetes, there are non-medication and medication approaches to achieve a healthy HbA1C

- Regularly monitor your eye health if you have diabetes to avoid conditions that may lead to vision loss

- Monitor your cholesterol levels and take action to reduce high cholesterol.

The good news is that if you’re eating right and exercising, you’ve taken the first steps to maintain blood vessel health. If, after eating right and exercising, these factors are still not well controlled, you may need to work with your doctor and use medications as prescribed.

Talk to your health care team about checking your blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar. Many pharmacies also have programs to help with high blood pressure and diabetes; check with your local pharmacist to see if they offer services for these conditions.

Topic:

Smoking and Alcohol

Don’t smoke and if you drink alcohol, drink less.

Cigarette smoking

Studies have shown that smoking increases the risk of Alzheimer disease and may increase the risk of other dementias. In some large studies, smokers had close to double the risk of developing dementia. On repeated cognitive testing, people who smoke show greater annual declines than non-smokers.

This reinforces the need to quit smoking, especially for those aged 65 or older, to help promote brain health. Of course, there are other non-brain-related benefits of quitting smoking such as decreasing risk of stroke, heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, cancer, and chronic lung diseases (like COPD).

The Smokers’ Helpline can help you quit successfully, or talk with your health care team. Many pharmacies also offer smoking cessation programs.

Alcohol use

Heavy drinking is associated with brain changes, cognitive impairment, and dementia. People with alcohol use disorders have a higher risk of dementia, and they have an earlier onset as well.

More recent Guidelines from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction have highlighted many of the other health risks associated with alcohol consumption. Their report underlines that even a small amount of alcohol can be damaging to health, and that drinking less is better.

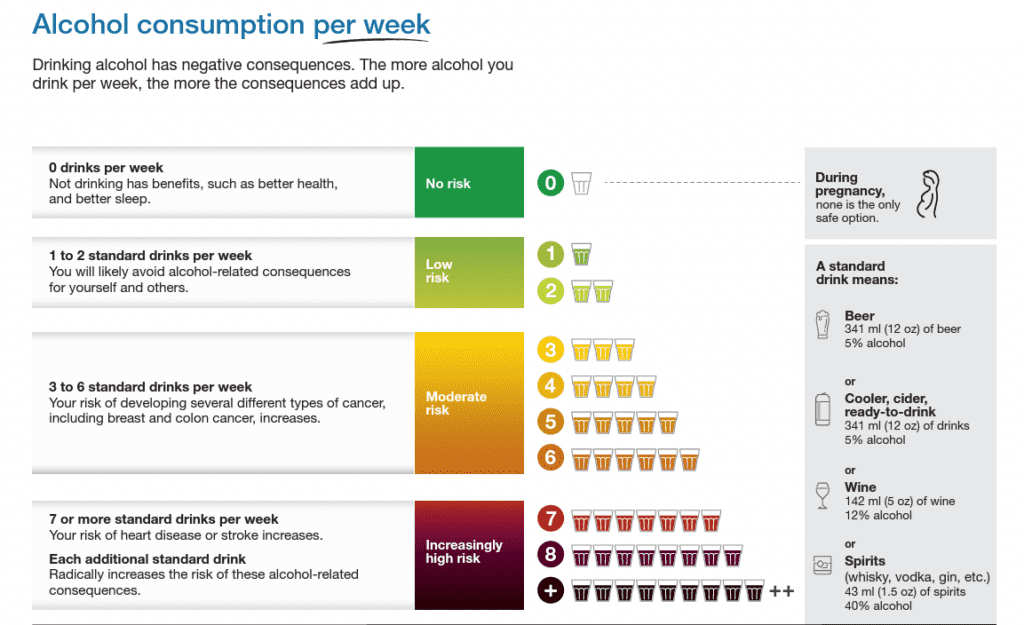

Have a look at the CCSA infographic which outlines different levels of health risks based on the number of drinks per week. Any amount over 2 standard drinks per week is considered a moderate or higher risk to your health.

However, if you’re cognitively impaired or it’s impacting your sleep, little or no alcohol may be recommended. Older adults are more sensitive to the effects of alcohol and will be more impaired when consuming the same amount of alcohol as when they were younger. It can also increase your risk of a traumatic brain injury, which also increases your risk of dementia.

Heavy drinking should be avoided by people of all ages, regardless of their level of cognitive function. If you have an alcohol use disorder, treatments may reduce your risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

Ways to drink less

Here are some suggestions from the CCSA on some helpful ways to reduce your alcohol use.

- Count how many drinks you have in a week.

- Set a weekly drinking target.

- If you’re going to drink, made sure you don’t exceed 2 drinks on any day; 1 if you are older.

- You can reduce your drinking in steps. Every drink counts: any reduction in alcohol use has benefits.

Tips to help you stay on target

- Stick to the limits you’ve set for yourself.

- Drink slowly.

- Drink lots of water.

- For every drink of alcohol, have one non-alcoholic drink.

- Choose alcohol-free or low-alcohol beverages.

- Eat before and while you’re drinking.

- Have alcohol-free weeks or do alcohol-free activities.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2023. Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health, Public Summary: Drinking Less is Better (Infographic).

Learn more about Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health

Key messages from this topic

- Don’t smoke

- If you drink alcohol, it’s better to drink less

Topic:

Cognitive and Social Activity

Stay curious, stimulate your brain, and stay social.

Cognitive activity and brain exercises

Research has shown that activities that incorporate both cognitive and physical activities provide the most benefit with respect to promoting brain health. For example, dance or tai chi involve the benefits of aerobic exercise and cognitive training to learn new sequences of movements that challenge a person’s memory, attention and visual-spatial abilities.

Currently, there’s a lot of emphasis on cognitive-based training or brain-training exercises, which include activities such as video games, computerized training and interactive television-based training. Although some studies have shown that brain training improves function for that activity, and may even enhance your overall brain function, we don’t know what the best cognitive training activities are, what the long-term benefits may be and if it will help prevent dementia.

Brain-training games can be fun and have some potential for benefit. You should pick brain-training activities that you enjoy, and those that don’t cost too much money because paying more money doesn’t mean a higher chance of benefits to overall brain health.

Try to find activities with some degree of ‘desirable difficulty’: these are activities that are just the right amount of challenging. They are activating your brain in new and exciting ways such that you are learning new things; but they aren’t so challenging as to be frustrating. There is also some emerging evidence that more passive types of activities – like watching tv – are less stimulating than more active tasks, like using a computer (where you have to input something). Activities don’t have to be fancy brain-training games either; things like reading, puzzles, or trying to learn a new language can all stimulate the brain.

Social activity

Studies have also shown that low social participation, less frequent social contact, and feelings of loneliness are all associated with increased dementia risk.

Staying socially active has been associated with better brain function in some studies. However, there is no high-quality evidence to suggest that specific types of social interventions improve cognitive function.

When possible, the simple pleasures of volunteering in your community, participating in church or spiritual groups and visiting with your family and friends can help reduce social isolation and feelings of loneliness.

Engaging in conversations requires us to pay attention, remember what others are saying to us, find our words, and put together clear thoughts, all of which may help us stay mentally sharp.

There are many community-based programs appropriate for age, gender, ethnicity, and interests to help people stay socially active as they age. There are also ways to find transportation if that’s an issue for you. If you don’t know where to start, call 211 or consult 211.ca to learn about offerings in your area; or contact your local community centre or YMCA to learn about their programs to help you stay social.

Learn more about social isolation in this 20-minute e-learning lesson on the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal.

Key points from this topic

Stay curious, stimulate your brain, and stay social.

Topic:

Other Conditions and Rx

Hearing and vision loss, traumatic brain injury, medication side effects, and other considerations.

Hearing and vision loss

Hearing and vision loss have a negative impact on both our functional ability and our social and emotional well-being. They affect our ability to communicate and participate in social activities and can impact our safety and independence as we age.

Hearing and vision loss can also increase the risk of falling, which can have a substantial impact on a person’s short and long-term physical mobility. A recent study done by Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the National Institute of Aging found that older adults with a 25-decibel hearing loss (classified as mild) were nearly three times more likely to have a history of falling. Furthermore, every additional 10-decibels of hearing loss increased the chances of falling by 140%.

Dementia risk and hearing loss

Those with moderate hearing loss are at 3-times the risk for developing dementia. In fact, it’s estimated that there is a 7% increased chance of developing dementia compared to someone without this risk factor. This is more than the risk associated with depression and lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity.

Things you can do about your hearing

Getting a hearing test in mid- and late-life is a good first step. If a deficit is found, there are several technologies and useful strategies that you can use on a daily basis to improve your hearing.

Be proactive about your hearing by following these 3 steps:

- Reduce your risk of hearing loss by protecting your ears from excessive noise exposure.

- Get your hearing checked.

- Use hearing aids if you have hearing loss

You can learn more about hearing loss and cognitive impairment in this series of blog posts from the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal, and this video from the iGeriCare website.

Dementia risk and vision loss

New evidence shows that untreated vision loss is associated with an increased risk for dementia.

Have your eyesight tested routinely and wear corrective lenses if required. If you develop cataracts, have them treated, and if you have diabetes, control your blood sugar to reduce your risk of diabetic retinopathy.

Traumatic brain injury

A traumatic brain injury is an injury that affects how the brain works. Some brain injuries may be considered ‘mild’ – like a concussion – and others more ‘severe’, if there is a skull fracture or a hit to the head that causes bleeding in the brain. Traumatic brain injury is also sometimes referred to as ‘acquired brain injury’ or ‘head injury’.

Most injuries that occur each year are mild traumatic brain injuries or concussions. This is caused by:

- A bump, blow, or jolt to the head, or

- By a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move quickly back and forth.

This sudden movement can cause:

- The brain to bounce around or twist in the skull

- Chemical changes in the brain

- Stretching and damaging brain cells

These changes in the brain lead to symptoms that may affect how a person thinks, learns, feels, acts, and sleeps.

What you can do to try to prevent a traumatic brain injury

Here are a range of actions you can take to try to prevent head injuries.

- Buckle up every ride

- Wear a seat belt every time you drive – or ride – in a motor vehicle.

- Never drive while under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

- Wear a helmet when you ride a bike

- Prevent falls

- Talk to your doctor to evaluate your risk for falling, and talk with them about specific things you can do to reduce your risk for a fall.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist to review your medicines to see if any might make you dizzy or sleepy. This should include prescription medicines, over-the counter medicines, herbal supplements, and vitamins.

- Have your eyes checked at least once a year, and be sure to update your eyeglasses if needed.

- Do strength and balance exercises to make your legs stronger and improve your balance.

- Make your home safer.

- Talk to your doctor to evaluate your risk for falling, and talk with them about specific things you can do to reduce your risk for a fall.

Learn more about fall and injury prevention on the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal and on the Parachute website.

Learn more about brain injury from the Ontario Brain Injury Association.

Depression

Studies have shown that the presence of depression nearly doubles the risk of developing dementia. However, it is a bit of a complex risk factor: depression might be a risk for dementia, but in later life dementia might cause depression.

What you can do about depression?

Treatment might help reduce the risks of cognitive decline. There are both non-drug and drug treatments available for depression.

Learn more about major depressive disorder and its treatment by exploring that topic on this website.

Conditions that affect your oxygen levels

There are a variety of medical conditions that might lower how much oxygen is getting to your brain, which can affect your memory, thinking, and overall brain function. These include conditions such as:

- congestive heart failure

- chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) like chronic bronchitis and emphysema

- anemia (low blood hemoglobin levels)

- sleep apnea

What you can do about it

If you have any of these conditions, work with your health care team to manage them as best as possible, to maximize the amount of oxygen getting to your brain.

Air pollution and second-hand smoke

An emerging area of interest and relatively new risk factor is the effects of air pollution and second-hand smoke on the brain. It’s possible that air pollution has similar effects on the brain as cigarette smoking, contributing to effects on blood vessels and possibly other toxic effects on the brain as well.

What you can do about air pollutants

Where possible, reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke to reduce your risks of dementia. It will also have positive effects on your lung health and other health outcomes as well.

Medication adverse effects

Several medications have the potential for adverse effects on memory and cognitive function. Medications such as benzodiazepines (widely used to treat anxiety or insomnia), the ‘Z-drugs’ or sleeping pills like zolpidem (Ambien) and zopiclone (Imovane), some antidepressants, and many pain medications such as opioids (also known as narcotics) can result in significant cognitive impairment.

Watch out for medications that have anticholinergic side effects, such as Benadryl, Gravol, older antidepressants like amitriptyline (Elavil), and some bladder medications like oxybutynin (Ditropan) and tolterodine (Detrol).

Many of these medications can also have adverse effects on mobility and increase the risk of falls.

| Medication type | Example |

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam (Ativan), alprazolam (Xanax) |

| Sleeping pills | Zolpidem (Ambien), zopiclone (Imovane) |

| Opioids | Morphine, hydromorphone (Dilaudid) |

| Anticholinergic drugs | Benadryl, Gravol, amitriptyline (Elavil), oxybutynin (Ditropan) |

What you can do about medication adverse effects

It’s important to review your medications regularly with your health care team to reduce your risk of serious side effects. Many pharmacies offer services – like Ontario’s MedsCheck Program for people taking a minimum of three medications – where they can help to review your medications.

Talk with your doctor about whether ‘deprescribing’ some medications slowly and safely might make sense for you. Deprescribing is the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or slowly coming off of medication that might be causing harm, or no longer be of benefit. You can learn more about it on the deprescribing.org website.

Key points about this topic

- Hearing and vision loss are significant modifiable risk factors for dementia, and are also associated with increased risks for falls and social isolation. Therefore,

- protect your ears from excessive noise exposure

- get your hearing checked

- use hearing aids if you have hearing loss

- have your vision checked, wear corrective lenses if required, and treat conditions such as cataracts

- Prevent head injuries by wearing a seatbelt and trying to reduce your risk of falls

- If you have depression, get it treated

- Manage any conditions that lower your oxygen levels

- Where possible, reduce your exposure to air pollution and second-hand cigarette smoke

- Periodically review your medications with your health care team to ensure you are getting maximum benefit and minimizing adverse effects on your memory and thinking

Topic:

Summary

Putting it all together.

Key points from this detailed overview

- There’s a lot you can do to promote brain health and reduce your risk of dementia

- Lifestyle changes with a range of modifiable risk factors may help you to prevent dementia

- The more you can implement, the better

- These healthy lifestyle habits are good for your overall health in addition to promoting brain health and reducing your risk of other chronic conditions like cancer

- Start with small changes that you can maintain – aim for progress, not perfection

What are the things you should do to promote brain health?

- Be physically active

- Keep moving and reduce your sedentary time

- Sleep well

- Manage your weight and diet

- Stay fit and maintain a healthy weight

- Eat healthy

- Look after your blood vessels

- Control your blood pressure

- Manage diabetes if you have it

- Monitor and manage your cholesterol

- Cigarettes and alcohol

- Don’t smoke

- Limit alcohol use

- Stay cognitively and socially active

- Stay curious and keep your brain stimulated

- Stay social

- Look after your hearing

- Manage other health conditions and medications

- Treat vision loss and monitor your eye health

- Prevent traumatic brain injury

- Review your medications regularly

Learn more on the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal at dementiarisk.ca.

Coming Soon! Free-Micro Learning Series

Subscribe to our upcoming email series on how to promote brain health and reduce your risk of developing dementia.

SubscribeCurated Resources

Helpful Links and Resources

Expert-selected websites and documents related to brain health topics.

-

Promoting Brain Health PDF Download

-

Download this 2-page handout with key points about brain health, as well as helpful resources.

View Resource -

Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines

-

Canada’s first ever 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults offer clear direction on what a healthy 24 hours looks like for Canadian adults aged 65 years and older.

View Resource -

Canada's Guidance on Alcohol and Health

-

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health provides people living in Canada with the information they need to make well-informed and responsible decisions about their alcohol consumption.

View Resource -

Blood pressure as we age: What is a healthy target?

-

Learn more about high blood pressure and healthy targets in this series of videos on the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal.

View Resource -

Social Isolation: Are You at Risk?

-

Discover the risk factors. Learn how social isolation impacts health and well-being, and practical ways to reduce your risk in this 20-minute e-learning lesson from McMaster University.

View Resource -

Diabetes: Types, tests and what to do if you are at risk

-

Learn about diabetes, prediabetes, and whether type 2 diabetes can be reversed in this series of video posts on the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal.

View Resource -

Dementia Risk Reduction - McMaster Optimal Aging Portal

-

Comprehensive info about dementia risk reduction on the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal

View Resource -

McMaster Optimal Aging Portal

-

Your source for healthy aging information you can trust.

View Resource -

Fountain of Health

-

Tap into five actions you can take to maximize your health and happiness. Use The Wellness App assess your health and resilience, set doable goals and track your progress.

View Resource

References

Evidence-based references that informed this topic.

About this Topic

The latest scientific evidence on this topic, including the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2019 Guideline for Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia, and the 2020 report of the Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care, was used to develop this resource. In the development of the WHO’s guidelines, AMSTAR was used to assess the quality of existing systematic reviews and the GRADE methodology was used to develop the evidence profiles.

The content of this resource was reviewed and assessed for accuracy by our team of experts in geriatrics and mental health. There are no conflicts of interest. A panel of end-users reviewed the content and provided feedback on their user experience. This resource was first published on February 19, 2023, and was adapted from the “How to Promote Brain Health” lesson on iGeriCare.ca and the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal.

If you have questions or comments related to this resource please contact us at info@healthhq.ca.

References by Topic

The scientific references for each topic area are outlined below:

Physical Activity & Weight Management: References 1–6

Diet & Nutrition: References 6–10

Vitamins, Supplements & Anti-Oxidants: References 11,12

Coconut Oil: Reference 12

Blood Vessel Health: Reference 3

Smoking & Alcohol Use: References 6,13–18

Brain Activity: References 3,6,19–24

Social Activity: References 3,25–27

Health Conditions & Drug Side Effects: References 3,28–34

Also:

Government of Canada. Dementia in Canada, including Alzheimer’s disease. Published 2017. Updated September 21, 2017. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-highlights-canadian-chronic-disease-surveillance.html

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet Commissions. July 30, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(20)30367-6/fulltext

National Institute on Aging. Cognitive health and older adults. Updated October 1, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/cognitive-health-and-older-adults

National Institute of Aging. What do we know about healthy aging? Updated February 23, 2022. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-do-we-know-about-healthy-aging

The Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for adults aged 65 years and older: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. 24-Hour Movement Guidelines. 2021. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://csepguidelines.ca/guidelines/adults-65/

References

1. Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;60:56-64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003

2. Hamer M, Chida Y. Physical activity and risk of neurodegenerative disease: a systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychol Med. 2009;39(1):3-11. doi:DOI: 10.1017/S0033291708003681

3. WHO. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines. 2019. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/risk_reduction_gdg_meeting/en/.

4. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Physical Activity Training for Health. 2017:1-5. www.csep.ca/guidelines.

5. Northey JM, Cherbuin N, Pumpa KL, Smee DJ, Rattray B. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(3):154 LP – 160. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096587

6. Dhana K, Evans DA, Rajan KB, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Healthy lifestyle and the risk of Alzheimer dementia: Findings from 2 longitudinal studies. Neurology. 2020. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009816

7. Petersson SD, Philippou E. Mediterranean Diet, Cognitive Function, and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(5):889-904. doi:10.3945/an.116.012138

8. Berti V, Walters M, Sterling J, et al. Mediterranean diet and 3-year Alzheimer brain biomarker changes in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2018;90(20):e1789-e1798. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005527

9. Baycrest. Which Foods Help the Brain: Brain Health Food Guide. https://www.baycrest.org/Baycrest_Centre/media/content/form_files/BHFG_optimized.pdf.

10. Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1007-1014. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.009

11. Rutjes AWS, Denton DA, Di Nisio M, et al. Vitamin and mineral supplementation for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in mid and late life. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(12). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011906.pub2

12. Swaminathan A, Jicha GA. Nutrition and prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:282. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00282

13. Schwarzinger M, Pollock BG, Hasan OSM, Dufouil C, Rehm J. Contribution of alcohol use disorders to the burden of dementia in France 2008-13: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Heal. 2018;3(3):e124-e132. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30022-7

14. Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C. Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:36. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-8-36

15. Vingtdeux V, Dreses-Werringloer U, Zhao H, Davies P, Marambaud P. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol in Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S6. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-9-S2-S6

16. Braidy N, Jugder B-E, Poljak A, et al. Resveratrol as a Potential Therapeutic Candidate for the Treatment and Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2016;16(17):1951-1960. doi:10.2174/1568026616666160204121431

17. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-09/2012-Canada-Low-Risk-Alcohol-Drinking-Guidelines-Brochure-en.pdf.

18. Butt P, Beirness D, Gliksman L, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Alcohol and Health in Canada: A Summary of Evidence and Guidelines for Low-Risk Drinking. 2011. http://www.ccsa.ca.

19. Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):1006-1012. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6

20. Gheysen F, Poppe L, DeSmet A, et al. Physical activity to improve cognition in older adults: can physical activity programs enriched with cognitive challenges enhance the effects? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):63. doi:10.1186/s12966-018-0697-x

21. Butler M, McCreedy E, Nelson VA, et al. Does Cognitive Training Prevent Cognitive Decline? Ann Intern Med. 2017;168(1):63-68. doi:10.7326/M17-1531

22. Miller KJ, Dye R V, Kim J, et al. Effect of a computerized brain exercise program on cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(7):655-663. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.077

23. Valenzuela M, Hons M. Can Cognitive Exercise Prevent the Onset of Dementia? Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials with Longitudinal Follow-up. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(March):3. www.consort-statement.org;

24. Chiu H-L, Chu H, Tsai J-C, et al. The effect of cognitive-based training for the healthy older people: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176742-e0176742. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0176742

25. Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Oude Voshaar RC, et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;22:39-57. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006

26. Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):647. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-647

27. Gates NJ, Rutjes AW, Di Nisio M, et al. Computerised cognitive training for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in midlife. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD012278. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012278.pub2

28. Saczynski JS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Auerbach S, Wolf PA, Au R. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2010;75(1):35-41. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e62138

29. Prince M, Albanese E, Guerchet M, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2014: Dementia and Risk Reduction An Analysis of Protective and Modifiable Factors.; 2014. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf.

30. Lin FR, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):369-371. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.728

31. Kim SY, Lim J-S, Kong IG, Choi HG. Hearing impairment and the risk of neurodegenerative dementia: A longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15266. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33325-x

32. Gurgel RK, Ward PD, Schwartz S, Norton MC, Foster NL, Tschanz JT. Relationship of hearing loss and dementia: a prospective, population-based study. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(5):775-781. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000000313

33. Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:151-161. doi:10.2147/NSS.S134864

Learn More

Explore Our Other Topics

Anxiety Disorders

Understand the signs and symptoms of anxiety, its diagnosis, and treatment options.

Anxiety

Major Depressive Disorder

Understand the signs and symptoms of depression, its assessment, and treatment options.

Depression

Mild Cognitive Impairment

Review the causes of mild cognitive impairment, its diagnosis, and management.

Cognitive ImpairmentAbout this page

-

This page was developed by the Division of e-Learning Innovation team and Dr. Anthony J. Levinson, MD, FRCPC (Psychiatry). Dr. Levinson is a psychiatrist and professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behaviour Neurosciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University. He is the Director of the Division of e-Learning Innovation, as well as the John Evans Chair in Health Sciences Educational Research at McMaster. He practices Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry, with a special focus on dementia and neuropsychiatry. He is also the co-developer of the iGeriCare.ca dementia care partner resource, and one of the co-leads for the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal. He and his team are passionate about developing high-quality digital content to improve people's understanding about health. By the way, no computer-generated content was used on this page. Specifically, a real human (me) wrote and edited this page without the help of generative AI like ChatGPT or Bing's new AI or otherwise.

-

Dr. Levinson receives funding from McMaster University as part of his research chair. He has also received several grants for his work, from not-for-profit granting agencies. He has no conflicts of interest with respect to the pharmaceutical industry; and there were no funds from industry used in the development of this website.

-

October 31, 2024

-

Content was written and adapted based on credible, high-quality, non-biased sources such as MedlinePlus, the National Institutes for Mental Health, the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal, the American Psychiatric Association, the Cochrane Library, the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH) and others. See References below. In particular, evidence-based content about dementia risk reduction was also derived from the World Health Organization and the Lancet Commission reports.

-

The initial development of some of this content was funded by the Centre for Aging and Brain Health Innovation, powered by Baycrest. Subsequent funding was through support from the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal, with support from the Labarge Optimal Aging Initiative, the Faculty of Health Sciences, and the McMaster Institute for Research on Aging (MIRA) at McMaster University. There are no conflicts of interest to declare. Funding for this website was provided by the Labarge Optimal Aging Initiative and in-kind contributions from McMaster University and CAMH. There was no industry funding for this content.

Cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience possible on our website and to analyze our traffic. You can change your cookie settings in your web browser at any time. If you continue without changing your settings, we'll assume that you are happy to receive cookies from our website. Review our Terms of Use for more information.